How much weight did you gain in pregnancy?

With my daughter, which was my first full term pregnancy, I gained 55 pounds! For my son, the total was 45 pounds! I gained a lot of weight. I didn’t worry about it. My midwives were supportive.

Ironically, I lost weight during both of my first trimesters due to being very ill from all day, aka morning, sickness. I went to see a nutritionist, and all of my caregivers were concerned I would not gain enough weight. Boy, were they wrong!

I looked enviously at my friends that seemed to only gain the weight of the baby, and I did have some worry I would not lose it all. I tried to focus on the moment and do what was right for my growing babies. Starving during pregnancy is not good for mother or child.

A new research study published in PLOS One found weight gain to be especially important for boys. This is the opposite of my personal experience, but my weight gain was so significant, I am sure it was enough.

Researcher Kristen J. Navara found:

Abstract

Background

Human males are more vulnerable to adverse conditions than females starting early in gestation and continuing throughout life, and previous studies show that severe food restriction can influence the sex ratios of human births. It remains unclear, however, whether subtle differences in caloric intake during gestation alter survival of fetuses in a sex-specific way. I hypothesized that the ratio of male to female babies born should vary with the amount of weight gained during gestation. I predicted that women who gain low amounts of weight during gestation should produce significantly more females, and that, if gestational weight gain directly influences sex ratios, fetal losses would be more likely to be male when women gain inadequate amounts of weight during pregnancy.

Methods

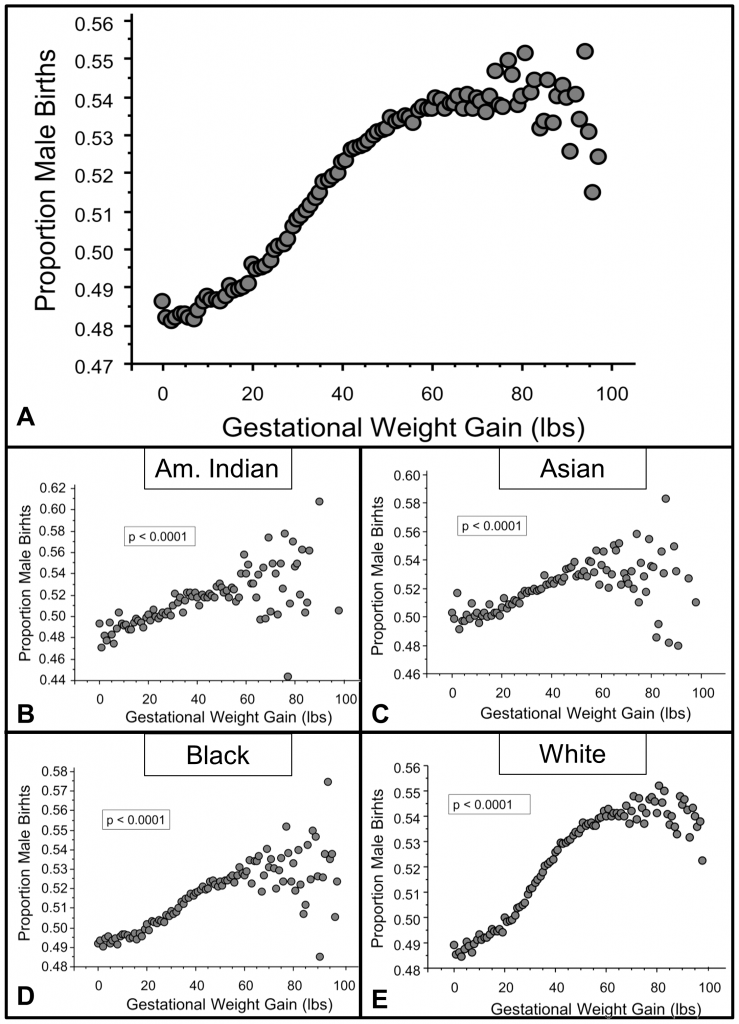

I analyzed data collected from over 68 million births over 23 years to test for a relationship between gestational weight gain and natal sex ratios, as well as between gestational weight gain and sex ratios of fetal deaths at five gestational ages.

Results

Gestational weight gain and the proportion of male births were positively correlated; a lower proportion of males was produced by women who gained less weight and this strong pattern was exhibited in four human races. Further, sex ratios of fetal losses at 6 months of gestation were significantly male-biased when mothers had gained low amounts of weight during pregnancy, suggesting that low caloric intake during early fetal development can stimulate the loss of male fetuses.

Conclusion

My data indicate that human sex ratios change in response to resource availability via sex-specific fetal loss, and that a pivotal time for influences on male survival is early in fetal development, at 6 months of gestation.

Male babies are more susceptible in utero to less than ideal conditions, and the results of this study are interesting to consider in relation to populations living in marginal, low socio-economic conditions.

Male embryos start life with higher rates of cell division and higher metabolic rates compared to females [5], [6]. These differences appear to extend through the second trimester, as male fetuses exhibit faster growth rates prior to the third trimester, after which the sex differences in growth rates appear to even out [7]. The result is a nearly 100 g weight difference between male and female newborns [8]. This disparity in growth rates between males and females indicates that nutritional requirements should also be sex-specific. Indeed, women carrying boys had 10% higher energy intake compared to those carrying girls [8]. Women with diseases that lower food intake or nutritional absorption such as anorexia, bulimia, and celiac disease, produce lower percentages of male offspring [9], [10]. Further, during times of famine, the sex ratio at birth declines, becoming female-biased [11], [12], Ethiopian women that were in a better nutritional state according to body mass and muscle indices had a higher percentage of male births, and Italian women who were thinner produced a lower percentage of boys [13]. On the other hand, women with binge-eating disorders produced significantly higher percentages of males [9] and rich individuals who likely have access to larger amounts of nutritious food also produce more male babies [14], [15]. The calorie intake per capita is also related to sex ratios at birth; countries with lower caloric intakes produce lower percentages of males at birth, likely due to higher rates of male fetal death [16]. These studies suggest that extreme decreases in energy intake are detrimental to the survival of male fetuses.

Prior to reading this study, I had no idea that male babies developed differently or had greater prenatal nutritional requirements.

Of course, sex is not determined by nutrition but by sex chromosomes. Nutrition, however, may play a part in the survival of fetuses. More boys may be miscarried when mothers are not meeting the nutritional needs of the sex.

My first pregnancy ended in miscarriage when I was in my early twenties. As any mother that has miscarried can relate, I often think about how old the child would be today, and what he would be like. I had many dreams that the child was a boy. Perhaps my poor, youthful vegetarian diet was the cause. (I still am a vegetarian and was for both of my complete pregnancies).

As reported in the New York Times:

“More than 13 million women in our study gained fewer than 20 pounds during gestation — this comes out to approximately 525,200 ‘missing’ males,” Dr. Navara said.

“For women who are older,” she added, “we do tests around 11 weeks to find chromosomal problems and we incidentally discover the sex. Maybe it’s worth doing that for everyone so that we can optimize the conditions necessary to survival.”

It’s interesting to consider, and I can’t help but think of the extra resources and strain these 525,200 “missing males” would put on our environment. That being said, if I was pregnant, I would want to do everything possible to ensure my baby’s growth, health, viability, and survival.

Leave a Reply