Sometimes I wish I was still an elementary school teacher when I think of the important issues of our day. I want to educate children so they can make choices and create solutions to the problems their ancestors have created.

In this time when science curriculum, such as evolution, is not taught in certain districts and states, it concerns me what children are learning about climate change. Many states like West Virginia, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Wyoming have opposed the Next Generation Science Standards that ask students to:

Ask questions to clarify evidence of the factors that have caused the rise in global temperatures over the past century.

From human causes to how we can lesson our individual impact on the planet, there are many lessons that can be taught on climate change in schools. What I fear is climate change is being discussed briefly around Earth Day, sort of how multicultural education can take on a holiday approach.

I think it is important for children to understand that climate change is happening, especially when they may confront doubters in their families.

One approach I would use to teach climate change is the indicators. Many of these indicators are easily observed and tracked by students. I would start a school-wide program, in order that each class could compare data year-by-year.

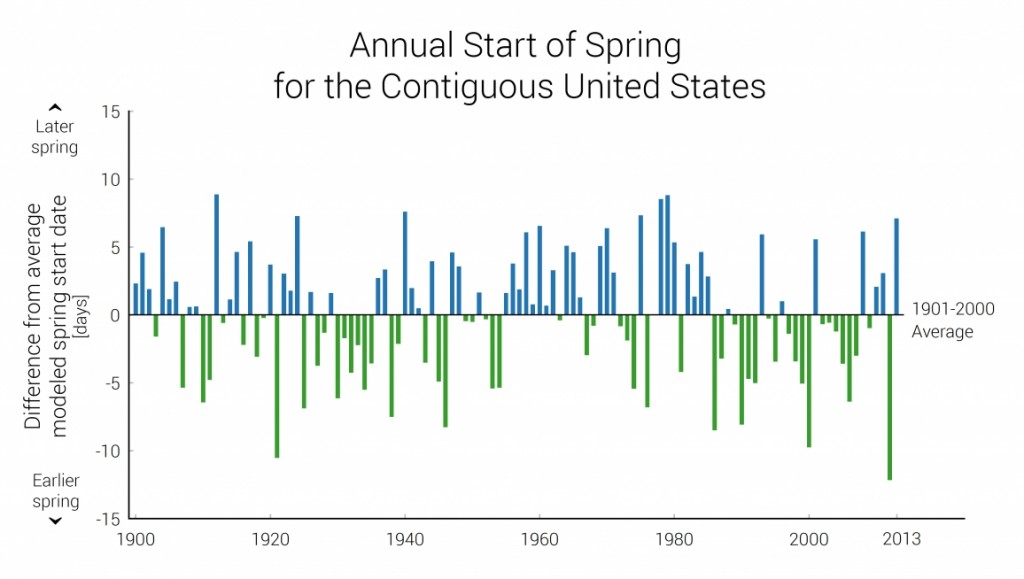

One of the climate change indicators the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), a group involving 13 governmental agencies, has identified is the start of spring.

This indicator estimates the annual start of spring on the basis of when growth can begin for temperature-sensitive native and cultivated plants. It can be used to monitor, assess, and predict variations and trends in spring timing at the national scale. Since 1900, the modeled start of spring (averaged over the contiguous United States) has varied within a three-week range. Since 1984, it typically has occurred earlier relative to the last century’s average, with the earliest spring start occurring in 2012.

The bars on the graph show the number of days by which the start of spring differs from the average start of spring during the last century. These values are calculated from a numerical model that simulates the accumulation of heat needed to bring plants out of winter dormancy and into vegetative and reproductive growth. The model is based on (1) long-term observations of lilac and honeysuckle first-leaf and first-bloom, collected by citizen science volunteers at hundreds of sites across the contiguous United States, and (2) daily minimum and maximum temperatures measured at weather stations. The annual start of spring can be estimated for any location where daily minimum and maximum temperatures are recorded. The modeled values correlate well with observed leafing and flowering in a number of native and cultivated species, such as winter wheat, pear, and peach varieties.

A trend toward earlier springs could have significant implications for agriculture, natural resource and hazard management, and recreation. Decision makers can use this indicator to anticipate climate impacts on habitats and species, optimize crop selection and yield, and assess the potential vulnerability of ecosystems to drought and wildfire.

Our family has been observing these changes for years with wild and domestic plants around our home. For example, the bears grass is blooming three weeks early this year. The irises also bloomed early in our yard.

Most schools have at least some plant life on their campuses. If not, children can plant perennials to track the start of spring. To copy the government study, lilac and honeysuckle could be used. Even observing the date of daffodil blooms would be interesting.

Experiencing observable climate change indicator data like the start of spring gives children hands on experience. When the data does not comply with the trend of earlier spring, great discussions can ensue and be used to explain why some of the public still does not accept the idea of climate change.

Over long term, the data should reflect the trend scientists are studying. Such data is hard to dispute. Students can brain storm the significance to our planet and human life. Why does an earlier spring even matter?

Photo credit: Honey Suckle by Tony Alter on Flickr Some rights reserved

Leave a Reply