Last month, the United States Deparment of Agriculture (USDA) released shocking information about the food we consume. Testing 10,187 food samples, the USDA found 85% of our fruits and vegetables contain pesticides residues. The testing was conducted in 2015 from food collected in California, Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas, and Washington.((https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/2015PDPAnnualSummary.pdf)) This is an increase of 26% over the previous year.

Although the findings are alarming, the USDA assures us our food supply is safe. According to the report titled “Pesticide Data Program Annual Summary, Calendar Year 2015”:

The PDP provides reliable data to help assure consumers that the food they feed themselves and their families is safe. Over 99 percent of the products sampled through PDP had residues below the EPA tolerances. Ultimately, if EPA determines a pesticide is not safe for human consumption, it is removed from the market.((https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/2015PDPAnnualSummary.pdf))

Despite these assurances, there is cause for concern. One pesticide we researched is currently proposed to be banned by the EPA. Furthermore, the report found the residue of 20 different pesticides on one strawberry. Eco Watch reports:

“We don’t know if you eat an apple that has multiple residues every day what will be the consequences 20 years down the road,” said Chensheng Lu, associate professor of environmental exposure biology at the Harvard School of Public Health. “They want to assure everybody that this is safe but the science is quite inadequate. This is a big issue.”

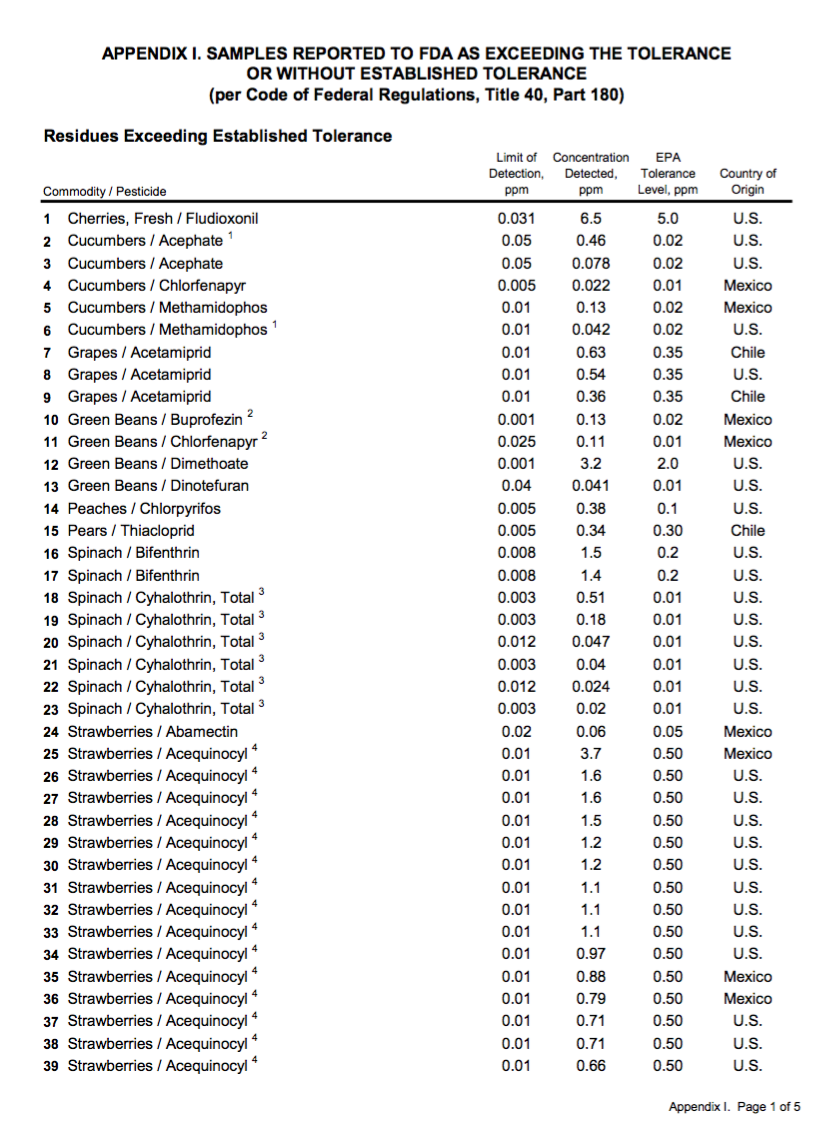

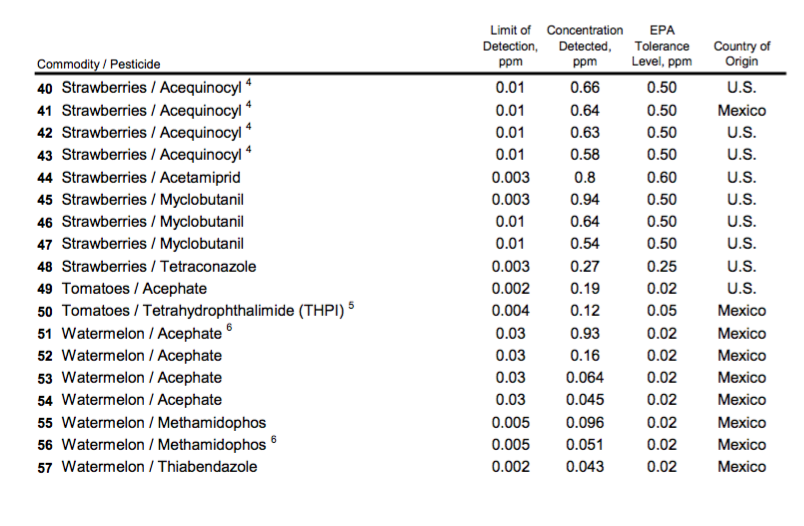

The USDA said in its latest report that 441 of the samples it found were considered worrisome as “presumptive tolerance violations,” because the residues found either exceeded what is set as safe by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or they were found in foods that are not expected to contain the pesticide residues at all and for which there is no legal tolerance level. Those samples contained residues of 496 different pesticides, the USDA said.

Spinach, strawberries, grapes, green beans, tomatoes, cucumbers and watermelon were among the foods found with illegal pesticide residue levels. Even residues of chemicals long banned in the U.S. were found, including residues of DDT or its metabolites found in spinach and potatoes. DDT was banned in 1972 because of health and environmental concerns about the insecticide.((http://www.ecowatch.com/usda-pesticide-exposure-2105041546.html?utm_source=EcoWatch+List&utm_campaign=dd825a54f2-MailChimp+Email+Blast&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_49c7d43dc9-dd825a54f2-85357185))

Eco Watch also points out that the USDA pesticide testing did not include glyphosate, the active ingredient in Monsanto’s RoundUp, which has been linked to an array of human health problems. The absence of this ubiquitous herbicide in the testing could stem from the fact the USDA was looking at pesticides not herbicides. It does not appear the USDA publishes a separate report for herbicide residue in our food supply.

Two years ago, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found fault with the testing:

Among other things, GAO found that FDA tests relatively few targeted (i.e., non-generalizable) samples for pesticide residues. For example, in 2012, FDA tested less than one-tenth of 1 percent of imported shipments. Further, FDA does not disclose in its annual monitoring reports that it does not test for several commonly used pesticides with an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established tolerance (the maximum amount of a pesticide residue that is allowed to remain on or in a food)—including glyphosate, the most used agricultural pesticide. ((http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-38))

The 2015 pesticide residue testing program included 97% fresh, frozen, and processed fruits and vegetables and 3% peanut butter both domestic and imported. Below is a chart of the commodities that exceeded USDA safe levels.

We used a novel study design to measure dietary organophosphorus pesticide exposure in a group of 23 elementary school-age children through urinary biomonitoring. We substituted most of children’s conventional diets with organic food items for 5 consecutive days and collected two spot daily urine samples, first-morning and before-bedtime voids, throughout the 15-day study period. We found that the median urinary concentrations of the specific metabolites for malathion and chlorpyrifos decreased to the nondetect levels immediately after the introduction of organic diets and remained nondetectable until the conventional diets were reintroduced.((https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1367841/))

THE UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY FOUND THAT TOXINS ARE ON AVERAGE 10 TIMES MORE POTENT FOR BABIES THAN ADULTS.((http://eyr.lil.mybluehost.me/2016/11/24/why-organic-homemade-baby-food-is-better/))

In fact, the Food Quality Protection Act Public Law 104-170 (1996) requires:

Consider the special susceptibility of children to pesticides by using an additional tenfold (10X) safety factor when setting and reassessing tolerances unless adequate data are available to support a different factor

The above study found that the pesticide chlorpyrifos immediately decreasted to nondetectable levels as soon as children switched to an organic diet. Although the USDA study found this pesticide to be in the acceptable range of tolerance for peaches, it was still detectable. According to the EPA, children are considered when setting tolerances.

We perform dietary risk assessments to ensure that all tolerances established for each pesticide are safe. These assessments account for the fact that the diets of infants and children may be quite different from those of adults and that they consume more food for their size than adults. We address these differences by combining survey information on food consumption by infants and children with data on pesticide residues to estimate their exposure from food. We also estimate exposure of other age groups such as women of reproductive age, ethnic groups and regional populations. ((https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-tolerances/setting-tolerances-pesticide-residues-foods))

Are children more sensitive to chlorpyrifos than adults?

Chorpyrifos exposure was linked to changes in social behavior and brain development as well as developmental delays in young laboratory animals. Other studies showed that chlorpyrifos affected the nervous system of young mice, rats, and rabbits more severely than adult animals.

Researchers studied the blood of women who were exposed to chlorpyrifos and the blood of their children from birth for three years. Children who had chlorpyrifos in their blood had more developmental delays and disorders than children who did not have chlorpyrifos in their blood. Exposed children also had more attention deficit disorders and hyperactivity disorders.

In general children may be more sensitive to pesticides than adults. One reason for this is that their bodies may break down pesticides differently. Children are also more likely to be exposed to pesticides when playing and may put their hands in their mouths more often than adults. Children may also be more sensitive to exposures because they have more surface area of skin for their body size than adults.((http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/chlorpgen.html))

The peaches from the US last year contained over the tolerance level at 0.38 ppm detectable chlorpyrifos, almost 4 times acceptable level. According to the EPA, “In October 2015, EPA proposed to revoke all food residue tolerances for the insecticide chlorpyrifos.” A final decision will be made in March 2017.((https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/proposal-revoke-chlorpyrifos-food-residue-tolerances))

When it comes to pesticide use in the US, the process is complex. Even though the the EPA wants to remove all use of chlorpyrifos from use due to human health and drinking water concerns, this action was blocked by the 9th Circuit Court in 2015 because of timeline issues for seeking further assessment. The new assessment found:

The revised analysis indicates that expected residues of chlorpyrifos on most individual food crops exceed the “reasonable certainty of no harm” safety standard under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA). In addition, the majority of estimated drinking water exposures from currently registered uses, including water exposures from non-food uses, continue to exceed safe levels even taking into account more refined drinking water exposures. Accordingly, based on current labeled uses, the agency’s analysis provided in this notice continues to indicate that the risk from the potential aggregate exposure does not meet the FFDCA safety standard. EPA can only retain chlorpyrifos tolerances if it is able to conclude that such tolerances are safe.((https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/PrePublicationCopy_16P-0280_2016-11-10.pdf))

The EPA proposes:

Because tolerances are the maximum residue of a pesticide that can be in or on food, this proposed rule revoking all chlorpyrifos tolerances means that if this approach is finalized, all agricultural uses of chlorpyrifos would cease.

According to USDA data there are approximately 1.2 million crop producing farms in the U.S. EPA estimates that more than 40,000 crop producing farms currently use chlorpyrifos to control a wide range of insect pests. Cost effective alternatives are available to control many of the pests targeted by chlorpyrifos. Some farms growing certain crops (e.g., broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, citrus, etc.) may be affected more than others by the loss of the use of chlorpyrifos. ((https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/proposal-revoke-chlorpyrifos-food-residue-tolerances))

Chlorpyrifos is just one pesticide that exceeded government tolerance levels in the USDA’s “Pesticide Data Program Annual Summary, Calendar Year 2015”. Digging a little deeper into the EPA, we find this pesticide will hopefully be removed from US markets by 2017. If we explored more pesticides that exceeded tolerance levels in the report, what might we find?

Leave a Reply