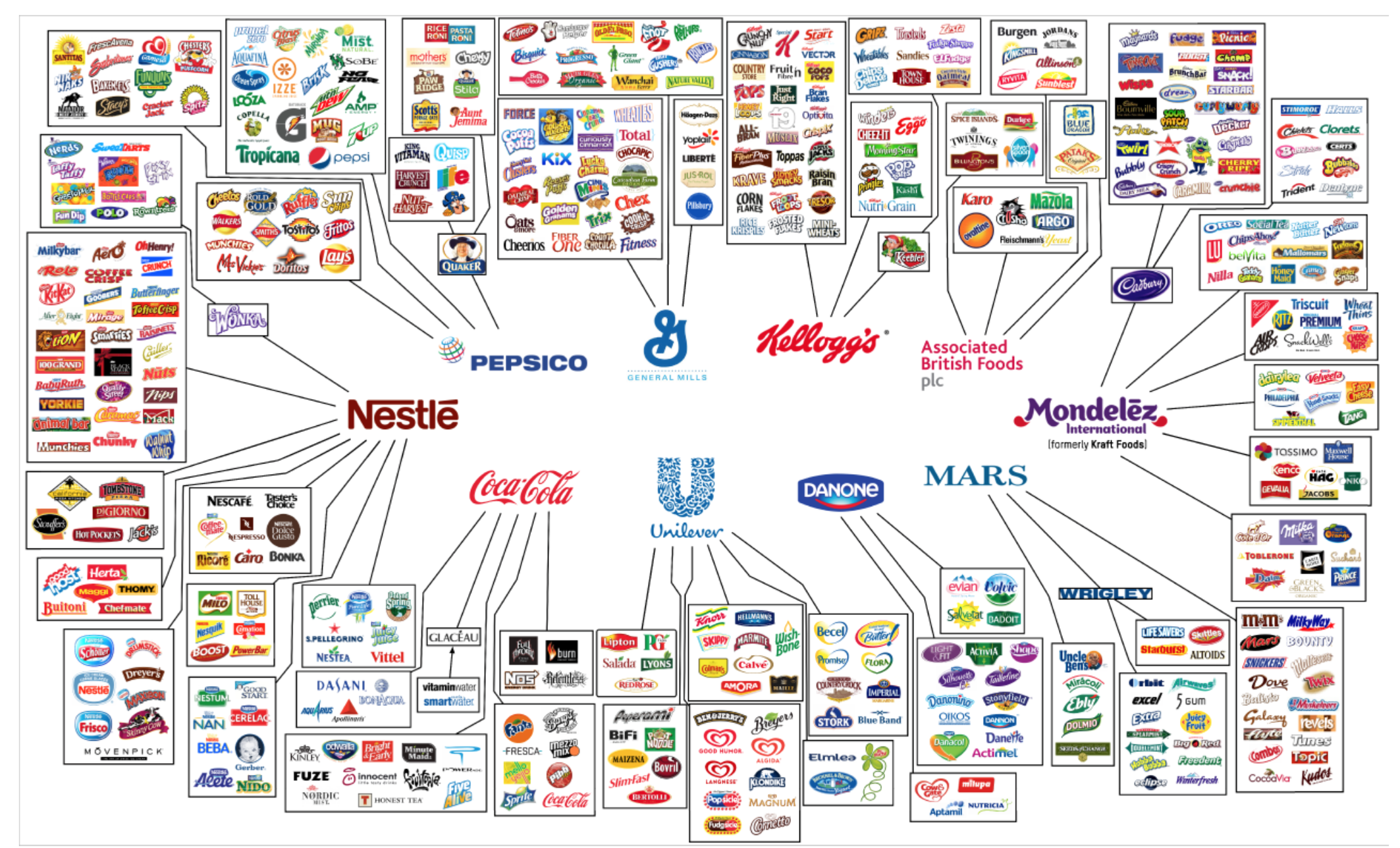

Food is a basic necessity of life. As consumers in the United States, we are offered an immense array of choices in grocery stores. This vast selection gives the illusion of diversity. In actuality, most food companies are owned by 10 larger corporations.

Food is a basic necessity of life. As consumers in the United States, we are offered an immense array of choices in grocery stores. This vast selection gives the illusion of diversity. In actuality, most food companies are owned by 10 larger corporations.

Oxfam has identified these companies as the “Big 10”.

- Associated British Foods (ABF)

- Coca-Cola

- Danone

- General Mills

- Kellogg

- Mars

- Mondelez International (previously known as Kraft)

- Nestle

- PepsiCo

- Unilever((http://www.nationofchange.org/2017/01/03/new-infographic-shows-10-companies-control-every-brand-know/))

It’s not just in America where supermarket shopping is big business. This trend has moved from Europe to Asia. Oxfam explains:

Walk into any supermarket in the world and you‟ll be immediately surrounded by a startling amount of food. Thousands of boxes of cereal, yogurt in every size and flavor, rows and rows of condiments and frozen food products – the modern-day American supermarket carries more than 38,000 products.In China, where no supermarkets existed in 1989, annual supermarket sales today total $100bn.

Although the sheer number of products suggests that consumers have a great deal of choice, the reality is that most of those cans, boxes and bottles are made by very few companies. Products once produced by smaller companies like Odwalla or Stonyfield Farms are now owned by the Big 10, and even older, more established products like Twinings (now more than 300 years old) have become just another brand on a company spread sheet.((https://www.behindthebrands.org/images/media/Download-files/bp166-behind-brands-260213-en.pdf))

What is the problem with 10 companies controlling so much of the world’s food supply?

Brand Values

There are many issues caused by the monopoly of the food supply. For food-conscious consumers who chose to eat organically and naturally, a brand’s values may be overshadowed by the parent company’s values. For example, many organic food and beverage companies that would seem to stand for GMO-labeling are owned by parent companies that do not support such labeling. For example, Santa Cruz Organic’s parent company contributed money via the Grocery Manufacturer’s Association to fight state GMO-labeling laws.

Oxfam identifies the following problems with the Big 10:

Important policy gaps include:

- Companies are overly secretive about their agricultural supply chains, making claims of ‘sustainability’ and ‘social responsibility’ difficult to verify;

- None of the Big 10 have adequate policies to protect local communities from land and water grabs along their supply chains;

- Companies are not taking sufficient steps to curb massive agricultural greenhouse gas emissions responsible for climate changes now affecting farmers;

- Most companies do not provide small-scale farmers with equal access to their supply chains and no company has made a commitment to ensure that small-scale producers are paid a fair price;

- Only a minority of the Big 10 are doing anything at all to address the exploitation of women small-scale farmers and workers in their supply chains.((https://www.behindthebrands.org/images/media/Download-files/bp166-behind-brands-260213-en.pdf))

How do communities move from subsistence farming to providing for global supply?

We have a global food system. Few communities exist that still farm primarily for local sustenance, even in remote regions. Take for example the apple orchards if the Kinnaur region in India. Climate change has enabled these Himalayan farmers to develop more land for apple production at higher elevations. When farmers shift to monoculture to meet the demands of a market, they lose their ability to be self-sufficient. Is this sustainable or socially responsible business practices?

According to Aghaghia Rahimzadeh‘s fascinating research described in “Political ecology of climate change: Shifting orchards and a temporary landscape of opportunity”:

Replacement of traditional crops with apples has meant that people now rely on purchasing their subsistence requirements from the market. Oral history interviews with elders provided similar statements as the following interviewee who emphasized the need to purchase flour, an important basis of the Kinnauri diet:

In those days, we had no money, but we were self sufficient for our own food. We had all our traditional crops to feed ourselves, like apricots and walnuts. We don’t have these traditional crops anymore, we don’t have as many apricot and walnut trees. Now we even have to buy our flour from the market. In those days, we had money problems, but we had our food to feed ourselves. Now we only have apples.

Interview, October 2012((http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452292916302004))

These apples may or may not be directly influenced by the Big 10. The Big 10 couldn’t tell you.

Oxfam expresses further concerns about the consolidation of the food and beverage industry:

This consolidation of the market-place has made it difficult for consumers to keep track of who produces which products and the „values‟ behind a brand. Additionally, already vulnerable small-scale farmers now have even fewer buyers for their products, leaving them with an increasingly weak bargaining position and with less market power.

But perhaps more troubling is that since the global food system has become so complex, food and beverage companies themselves often know little about their own supply chains. Where a particular product is grown and processed, by whom, and in what conditions are questions few companies can answer accurately and rarely share with consumers.((https://www.behindthebrands.org/images/media/Download-files/bp166-behind-brands-260213-en.pdf))

Farmers are hungry

What is perhaps most shocking about our global food economy is that the very people growing our food are often starving themselves.

Today, 450 million men and women labor as waged workers in agriculture, and in many countries, up to 60 percent of these workers live in poverty Overall, up to 80 percent of the global population considered „chronically hungry‟ are farmers, and the use of valuable agricultural resources for the production of snacks and sodas means less fertile land and clean water is available to grow nutritious food for local communities. And changing weather patterns due to greenhouse gas emissions– a large percentage of which come from agricultural production – continue to make these small-scale farmers increasingly vulnerable.((https://www.behindthebrands.org/images/media/Download-files/bp166-behind-brands-260213-en.pdf))

How can 80% of farmers be “chronically hungry”?

From forced and bonded labor to harsh working conditions, there is a story behind that box of cereal in the grocery aisle that is frightening. Your toddler may through a tantrum over the brightly colored box of sugary cocoa cereal. That is nothing compared to the pesticide exposure, long hours, and exploitation of women, men and children behind the label. Take for example cocoa grown in Ghana, where farmers make just 80 cents a day, not to mention the sustainability of the soil and water used in the production of ingredients.((https://www.behindthebrands.org/images/media/Download-files/bp166-behind-brands-260213-en.pdf)) All of this is hidden behind the Big 10.

Only about 1/3 of Americans are concerned about how their food is produced.((https://www.behindthebrands.org/images/media/Download-files/bp166-behind-brands-260213-en.pdf)) This concerning. We shop for our food without consideration of its production. Supermarkets enable us to disassociate from the source of our food. Even when we shop in local coops supporting natural and organic brands, the Big 10 are behind most of them.

Eating ethically is difficult in modern times with the conglomeration of food production. Local farmer’s markets and brands make it easier for consumers to connect with the source of their sustenance.

Leave a Reply